Kathy Acker, Clarion of Entropy

Published 15 December 1997 on the now-defunct website Other Rooms. A reflection.

Kathy Acker, who died November 30 [1997] of cancer at age 53, wrote about sex, the body and a sort of ecstatic despair like no other female author of our day. Throughout her career, she confounded the expectations of anyone who thought they had her number. In the end, her sense of freedom extended even to her choice of death.

Acker’s work was a bundle of contradictions, an assault on sense, and a scream against convention. Capable of an exalted lyricism, she more often wrote deliberately “badly.” Though she had a highly sharpened feminist and post-feminist sense, her female characters tended to express self-loathing and seek validation through offering themselves as pieces of meat. Here’s Juliet, having already died, still trying to seduce Romeo:

Juliet: No one ever said the world is perfect. Human beings have been mean to themselves and teach other in various uncountable ways ever since they were orangutans, yet all the time, as far as I know, no one’s ever died from fucking a corpse. men fuck corpses all the time. Most men would rather fuck corpses than other women. How do I know this? Because men pay prostitutes but they don’t pay other women to fuck. Yet the prostitutes don’t give a damn about the men who are humping on top of them, and if they feel anything, they like the money they’re earning. Now have you ever heard of a John dying, or even being put in jail?

Romeo: Rockefeller died.

Juliet: He was a politician.

Romeo: I’m so glad you’re not the woman I love because you’re a corpse so you can’t love in return.

Juliet: Most men would find that an inducement.

That’s from “My Death My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini,” one of three pieces in Literal Madness, and a classic example of Acker’s strategems. The book features Romeo and Juliet and several other characters from Shakespeare including a burlesqued IRA-filled version of “Macbeth,”, an “I” who seems to live in both 15th century Italy and the East Village circa 1980, the Lesbian Guerilla Army and some penguins, and an assortment of types. What it has to do with Pasolini, the gay Italian film director who killed himself around the time the book was written, I don’t know.

But it is typical of Acker’s work: Sex, violence and politics mixed up with characters and stories from literary classics and history. A character identifiable with the author (and sometimes called Kathy) who uses sex to manipulate people into loving her. A willingness to turn literature and narrative reality inside out. Acker’s books are like those fantastic exploded-view illustrations of mechanical devices, in which you can see every part labeled and floating near the part to which it is connected. Like these drawings, Acker’s writing explodes reality until you can see the underlying works; unlike them, the purpose is not to explain and make clear, but to create meaning through fantastic juxtapositions and bare, raw rendition.

This is the dream I have: I’m running away from men who are trying to damage me permanently. I love mommy. I know she’s on Dex, and when she’s not on Dex she’s on Librium to counteract the Dex jitters so she acts more extreme than usual. A second orgasm cools her shoulders, the young girl keeps her hands joined over the curly brownhaired’s ass, the wire grating gives way, the curly brownhaired slides the young girl under him his pants are still around his knees his fingernails claw the soil his breath sucks in the young girl’s cheek blows straw dust around, the mute young girl’s stomach muscles weld to the curly- haired’s abdominal muscles, the passing wind immediately modulates the least organic noise that’s why one text must subvert (the meaning of) another text until there’s only background music like reggae: the inextricability of relation-textures the organic (not meaning) recovered, stupid ugly horrible a mess pinhead abominable vomit eyes- pop-out always-presenting-disgust-always presenting-what-people-flee always-wanting-to-be-lonely infect my mother my mother, blind fingernails spit the eyes wandering from the curly-headed, the curly- headed’s hidden balls pour open cool down on the young girl’s thigh. Under the palmtrees the RIMAS seize and drag a fainted woman under a tent, a flushing-forehead blond soldier burning coals glaze his eyes piss stops up her sperm grasps this woman in his arms, their hands their lips touch lick the woman’s clenched face while the blond soldier’s greasy wine-stained arm supports her body, the young girl RECOVERED.

— Great Expectations

These passages give many clues as to what Acker was up to: dense physical and pornographic images vie with abstract literary theories; violence is always implied, often explicit; she creates an esthetic of the awkward, the ugly and the pathetic. All that is in a work named after a Charles Dickens novel and featuring characters and even whole sentences from that novel. To read a passage, or a whole book like that and ask “What happened?” misses the point. Acker’s point had much more to do with depicting the whole uncontrollable onslaught of society, filtered not for your consumption but for your burial.

The thing I like about this technique is the same thing that makes the Beatles’ “Revolution #9” not only one of my favorite songs but a turn-on. Acker’s vision is so complete and so personal that reading it makes me feel I’m inside her head, inside her body, screeching at top speed toward the present.

Acker’s work is also filled with dreams. Some of them are explicitly identified as such, like the passage from Great Expectations above. Some of them practically take over the work. In My Mother: Demonology, one of Acker’s later works and perhaps her masterpiece, travelling on a motorcycle in a dream recurs again and again until the journey finally leads somewhere. “The lack of dreams is the disappearance of the heart” reads one of the book’s subheads.

Hello, you wildness. Are you spreading your legs for me again? Inside your vagina is only freedom. I am not free to be mad and I will go to him and lay myself at his feet and say, “I’m your dog.” I have no idea how cause and effect are related in this land.

The man who’s claiming fathership of me is the Captain of the Pirates. I never knew him. This is why I talk about pirates. Freedom. (Besides, hairs grow out of their cocks.) And if dreams are dead, for the moment, I’m going to climb upon Chance, whose dog I will always be. I’m going to hump you until I have no more pussy hairs.

— My Mother: Demonology

One of the things I love about Acker’s work is her use of deliberately bald, “ugly” syntax, as in that passage. The syntax is so graceless it appears to be transliterated from some other language, but Acker did it to keep readers from conventional emotional associations with the characters and events. As she sacrificed the beauty of language to keep readers on the edge, she also sacrificed the dignity of her characters, especially the ones who seemed to represent herself, to her truth. Through the ugly language and the uglier events, the characters and the reader endure until all emerge at the end completely free.

Acker frequently used a persona, often an “I” in her books or a character called Kathy, whose search for love led her into ill- advised relationships, who was unable to earn enough love from others, whose sexual hunger in the service of love was uncontrollable. This character knows she’s “sick” but is also thrilled with the freedom implied at breaking all the rules:

You’ve got to get love. You’ve lost your sense of propriety. Your social so-called graces. You’re running around a cunt without a head. You could fuck anybody anytime any place you don’t give a damn who the person is except you really don’t want to get murdered any number of people except when the sex situations happen you have this idea lingering from the past maybe you shouldn’t fuck so much and so openly other people are looking down on you other people are thinking you’re shit. People misunderstand why you act the ways you do so they might harm you. You’ve already gotten beaten up once even though you kind of liked it. You’ve got to use your intellect to keep you in line, no insane sexual behavior no pleading and groveling for love, you don’t know the difference between friends and strangers, cause if you don’t use your arbitrary, it feels arbitrary, intellect to keep you in line, you’re going to go too far out, you’re beyond the limits of decent human behavior, pleasing and groveling on the ground, every time you get a scrap of love wanting twice as much more more, you’ve got to have more cause you know no one could love you cause no one’s ever loved you… You’ve got to get enough love all the love in the world to make it secure. You step on the people you meet. You use them for your insane desires.

— Kathy Goes to Haiti

MY CUNT RED UGH

GIRLS WILL DO ANYTHING FOR LOVE

— captions accompanying two drawings, by the author, of her genitals, in Blood and Guts in High School

Like other youths whose desire to avoid the straight nine-to-five world leads them into the sex industry, Acker worked for a while at peep shows while participating in the punk and New Wave scenes in New York in the late 70s. Acker’s first works focussed on the alternative arts scene in New York and the pervasiveness of sex and neuroticism. The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula and New York City in 1979 are filled with autobiographical, exhibitionistic passages that reveal her discovery of the dual curse and blessing of a young, adventurous woman’s sexuality.

But unlike other writers like Mary Gaitskill, whose early sex-filled writings led to a more mature emotionality, Acker stayed on the knife- edge of sex with all its implications. Her characters, creatures of the id for whom thoughts become instant reality, act out every middle-class sex fantasy of insatiability and decadence.

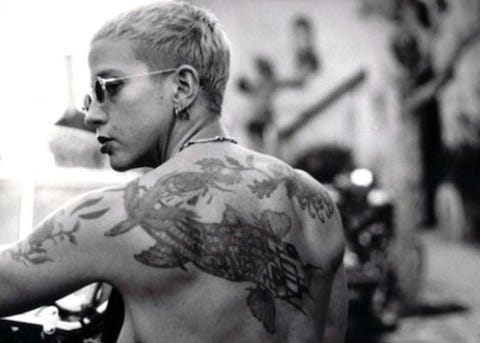

And like her characters, Acker seemed often willing to embody rebellion against convention. I knew her briefly. Tattooed and pierced, her body wiry and muscled through body-building, she rode a motorcycle and wore punk clothing long into her early 50s. In many ways she was the Kathy of her novels, both fearless and sensitive, blunt and manipulative, obsessed with sex and motorcycles. She was working on Pussy, King of the Pirates, her last novel. “While I work, I masturbate,” she told me. “In order to write about these girls” — the pirate girl characters of the book — “I have to masturbate, so I sit there and type and come and come and come.”

“It’s necessary to go to as many extremes as possible,” she wrote in New York City in 1979 . That’s a sentiment I admire, and agree with. The fearlessness with which Acker approached her writing, and her absolute dedication to it, I wish I could emulate. At least as far as writing goes. Acker, who refused western medical treatments, i.e. chemotherapy and radiation, to treat her recurring cancer, died in a Tijuana “alternative therapy clinic.” It’s hard for me to understand this choice, no matter how much I’m tempted to make some kind of connection between her art and her death. Perhaps it is necessary for someone who rejected the comforts of western literature to also reject the comforts of western medicine. I don’t know.

I do know that Kathy Acker touched many people, and that her friends were loyal and thought the world of her. I’ll go the memorial in San Francisco this weekend and try not to make any assumptions about the way things are. It’s what she would have wanted.

A selection of Kathy Acker’s books:

The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula (ISBN 0931106206) Paperback: Tvrt, June 1978

New York City in Nineteen Seventy-Nine (ISBN 0917061098) Paperback: Top Stories/Hallwalls, 1981

Blood and Guts in High School (ISBN 080213193X) Paperback: Grove Press, October 1, 1989

Literal Madness: Kathy Goes to Haiti/My Death My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini/Florida : Three Novels (ISBN 0802131565) Paperback: Grove Press, July 1, 1989

Empire of the Senseless (ISBN: 0802131794) Paperback: Grove Press, January 1, 1990

Hannibal Lecter, My Father (Native Agents Series) (ISBN: 0936756683) Paperback: Autonomedia, June 1991

My Mother: Demonology (ISBN: 0802134033) Paperback: Grove/Atlantic, October 1, 1994

Pussy, King of the Pirates (ISBN: 080213484X) Paperback: Grove/Atlantic, January 1, 1997

Bodies of Work : Essays (ISBN: 1852424257) Paperback: Serpents Tail, October 1, 1997

Acker’s obituary in the New York Times:

New York Times, 3 Dec 1997: Kathy Acker, novelist and performance artist, dead at 53